Celiac disease (coeliac or gluten intolerance) is defined as a permanent intolerance to gluten. It damages the small intestine but resolves whenever gluten is removed from the diet. Thus, it is a food sensitivity specific to gluten.

Most common sources of the gluten are wheat, barley, rye and few other grains. But not oats (unless contamination during processing).

When the gluten from these foods comes into contact with inner lining of small intestine, it causes inflammation and damage to the absorptive surface. Hence, a compromised surface reduces fluid secretion, mal-absorption, and destruction of the small intestine’s lining.

This damage to the intestine causes lower absorption of fat and micro-nutrients, e.g., iron, folate (B9), and fat-soluble vitamins from the foods. They all end up in stool without being absorbed. This can cause serious malnutrition.

Order an at-home celiac genetic test.

Genetic Testing and Disease Inheritability – role of genetics on health.

The Differences Between Genetic and Antibody Celiac Tests - And which one to order.

Food Sensitivity – Allergy, Intolerance, and Celiac Disease.

Food Allergies vs Food Sensitivities: What’s the Difference? - a few simple steps to differentiate.

Diurnal Salivary Cortisol – Risk Factors.

Celiac Genetic Crash Course – Tips from Healthieyoo.

The immediate effects of celiac disease include abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, fatigue, and mouth sores. Many other symptoms are often observed. These may include:

Chronic diarrhea

Weight loss

Bloating (abdominal distention – or expansion) in almost half of the people

Chronic fatigue

Iron deficiency (sometimes with anemia) due to improper absorption of nutrients

Recurring abdomen pain

Canker sores (aphthous stomatitis) – benign and non-infectious mouth sores

High levels of amino-transferase enzymes

Long term impacts include

Osteoporosis and reduced bone mineral density

Reduced spleen function

Infertility or frequent miscarriages

Short stature

Neurological disorders

Ulcers in the intestine

These symptoms may not always be as clearly visible. Yet, the inner lining of small intestine may be completely damaged. Fortunately the problem resolves upon removal of gluten from the diet and re-appears on re-introduction.

The main culprit in celiac is gluten from wheat, rye, barley, and the wheat-rye hybrid triticale.

Broadly speaking, many celiac disease-activating proteins are called “gluten”.

However, strictly speaking, gluten is the scientific name for the disease-activating proteins only in wheat.

Gluten in wheat has two major protein fractions called gliadins and glutenins. Both of these contain the celiac-activating proteins. In fact, wheat, rye, and barley are related in their origin.

The equivalent closely related proteins in barley and rye are hordeins and secalins, respectively.

It’s not the gluten, it’s the excess proline content in wheat, rye, and barley that makes the body hard to digest it.

One theory is that large chunks of proteins inside the small intestine remain without fully digesting. They do not break down into smaller peptide ingredients. Thus, these undigested peptides cross the intestinal lining where they find the appropriate pathways to react.

Oats are rare to cause celiac, although they often contaminate during processing. Oats are more distantly related and the equivalent proteins, called avenins. They are extremely rare to cause celiac, especially in moderation.

Rice, corn, sorghum, Job’s tears, millet, and tef are even more distantly related and not known to cause celiac.

Wheat

Rye

Barley

Malt

Kamut

Spelt

Couscous

Semolina

Triticale (wheat-rye hybrid)

Bread

Pizza

Pasta

Cakes

Cookies

Crackers

Cereals

Chips

Beer

Chicken broth

Candy bars

ketchup, mustard, sauces, dressings, syrups, cheese spreads, marinades

Coatings, flavorings, starch, creamer (non-dairy) and food mixes

Malt, ice-creams, soups, stuffing, thickeners, sausage

Tooth paste

Glues, pastes

Medication

Cross-contamination during processing and handling

Testing for gluten intolerance can be a long arduous process. Celiac may be complicated to diagnose as symptoms may never show. And it may take weeks or months of gluten-free diet to become free of symptoms.

Four out of these five key conditions are necessary for celiac confirmation as part of serological screening:

Clear symptoms of diarrhea, fatigue, abdominal pain.

An IgA antibodies test for tissue trans-glut-aminase (tTG) which is highly sensitive. Also, an IgG test to avoid false negatives (has very high specificity).

Positive for DQ2 or DQ8 genes (almost everyone with celiac have these genes).

Biopsy to confirm damage to small intestine lining and missing vili.

Response to gluten-free diet showing a decrease in symptoms when gluten is removed from food.

No.

One needs to be positive for certain genes to develop gluten intolerance as almost 100% cases of celiac have DQ2 or DQ8 genes.

Not everyone testing positive may have celiac, but certain genes are necessary to develop the intolerance. That’s because they produce antibodies that bind to gluten and cause the inflammation. And almost 40% of the western population has DQ2 or DQ8 genes but only about 1% have celiac.

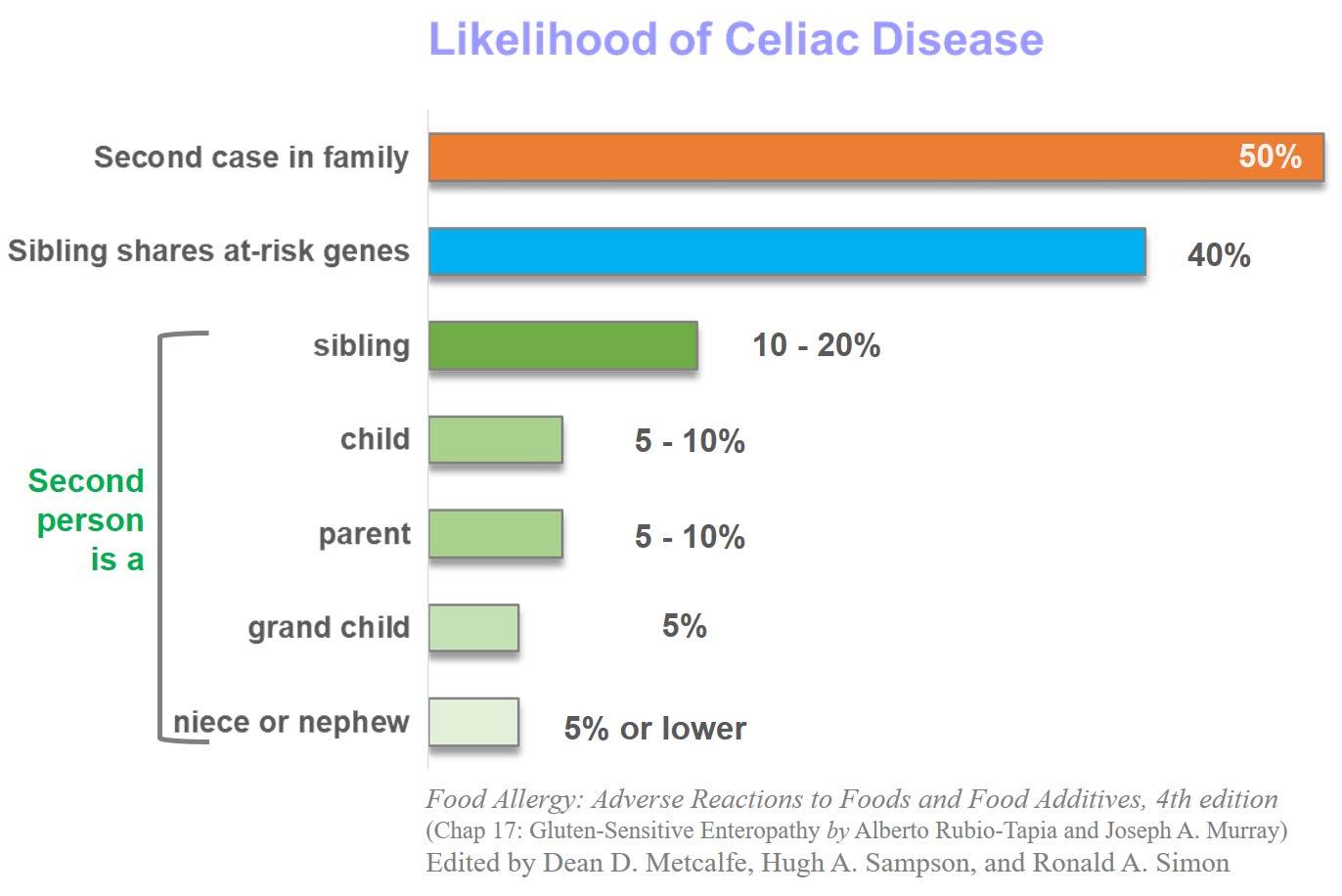

Almost 50% of first relatives are affected and a genetic test for DQ2 or DQ8 genes can help assess their risk. Celiac is almost twice more prevalent in women than men.

Children under the age of 3 years disproportionally show the symptoms as they first come in contact of gluten after weaning. The symptoms may be difficult to diagnose at this age making the situation worse.

Celiac may not show any symptoms at all.

In fact, experts believe only about 1 in 100 people are correctly diagnosed for multiple reasons. Symptoms may not always be clear and often overlap with other conditions. They may require multiple steps for final diagnosis which may not be guaranteed.

It may be difficult for some people to recognize that wheat, the main ingredient in their diet, can cause such a life threatening condition.

The following three key steps demonstrate how genes affect celiac:

The high proline content in the gluten from wheat, barley, and rye makes it harder to digest and break down in the intestine.

Subsequently, the tissue trans-glut-aminase enzyme (tTG) converts the undigested protein into a form that binds to the antibodies

And, the DQ2, DQ8 genes produce the antibodies that bind with the gluten peptide molecules

Several other findings shed light on this pre-disposition:

Almost 90-95% or more celiac patients carry DQ2.

Another 5-10% carry DQ8.

Thus combined DQ2 and DQ8 are present in almost 100% of patients.

In fact, higher the DQ2 molecules in the DQ system, higher the chances of celiac. For example, only about 2% have DQB1 genes, but they may be almost 25% of known celiac cases. A total of 39 genes have been identified but most have much lower correlation to celiac disease.

Celiac is rare in Japan where the DQ alleles are also rare (only two reports as of 2006).

Celiac clusters around families, suggesting a strong genetic bias.

Absence of certain genes can preclude any risk of celiac, although positive test may not always mean positive for celiac.

Almost 50% of first relatives may be positive and a genetic test for DQ2 or DQ8 genes can help assess their risk.

A history of genetic dependence of celiac tells a clear story of family dependence:

Although about 1% of the population has celiac, almost 5-15% of family members show gluten intolerance in affected families

In 70-75% of identical twins, both were positive whenever one of them had celiac. This is much higher than other auto-immune diseases of Type 1 diabetes (36%), Crohn’s disease (33%), and multiple sclerosis (25%)

People with these other autoimmune disease tend to show higher rates of celiac

It is not clear why some people do not have gluten intolerancedespite genetic pre-disposition.

Because genes, environment, and foods with gluten play a complex role in celiac, it may not always be possible to fully appreciate the roles of individual contributor.

It is also possible that despite having celiac, the symptoms may never be clearly visible.

Often a biopsy may be the only method to assess the damage to intestinal wall but may not be available without signs of symptoms.

Celiac is an under-diagnosed condition and only the tip of the ‘celiac iceberg’ show clear symptoms.

Also, the recent westernization of diets across the globe and more awareness allows more people to identify their symptoms.

A simple celiac genetic test with a saliva swab is sufficient to assess the risk.

A 2012 study by the New England Journal of Medicine says, “testing for HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 may be useful in at-risk persons (e.g., family members of a patient with celiac disease)”. Such testing has a “high-negative predictive value, which means that the disease is very unlikely to develop in persons who are negative for both HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8”.

In fact, “Up to 97% of cases”, the HLA phenotypes are prerequisite for celiac.

Another recent study by Mayo Clinic study calls for screening of family members of celiac patients for wider screening to assess the risk.

There is no known cure for celiac.

A lifelong adherence to gluten-free diet is the only known therapy.

A simple celiac swab test can check the genetic risk of celiac disease for those suspecting gluten intolerance even if their symptoms are difficult to observe.

Otherwise, a serological screening is necessary which includes a biopsy of small intestine and a blood test.

Celiac is historically a western disease, however, recent studies show that’s no longer true.

An Italian study of over 17,000 middle school students found 7.5% (or 1289) tested positive for the initial IgA, IgG blood test. About 0.5% (or 82) were positive for celiac. Therefore, 1 in 184 students had celiac, and 6 out of 7 were previously unknown for celiac.

A Swedish study of approx. 1900 adults showed 1 in 254 had celiac disease.

In a US study 1 in 250 people had celiac.

An Irish study found a higher ratio of 1 in 122 people with celiac, although the dataset was relatively smaller.

Study of 2500 healthy individuals in Tunisia, in North Africa, found 1 in 355 had celiac disease.

The highest ever occurrence of 5.7% has been reported in Algeria among the Saharawi tribes of Sahara desert. They have high frequency of DQ2 genes and have recently changed their dietary habits due to war.

An extensive review of non-western countries have identified almost similar rate of celiac across the world. This includes Africa , India, East Asia, Latin America, Middle East, South America, and Australia.

Diet is a significant factor in celiac prevalence. For example, in northern India, hospital studies show about one-percent children had celiac. In southern India, where rice is the staple food, celiac appears to be rare.

So far, 39 genes have been identified for celiac. However, almost all cases have DQ2 or DQ8 as the main gene responsible for the disease.

The DQ2, DQ8 genes are key to developing the response to gluten sensitivity.

The DQ2, DQ8 genes produce molecules that bind with the gluten peptide molecules. This molecular combination triggers an immune response.

However, the gluten molecules need to be negatively charged. That role is carried out by trans-glut-aminase enzyme (tTG) which converts the undigested protein into a negatively charged form. This binds to DQ2, DQ8 molecules (the presence of this excess tTG is the first step in testing for celiac)

The high proline content in the gluten from wheat, barley, and rye makes it harder to digest. Without breaking down in the intestine, the undigested gluten becomes readily available for the tTG molecule.

The immune response to gluten happens through activation of T-cells. These cells constantly search for foreign particles and other compromising entities the body. The DQ-gluten complex very effectively activates these T-cells. But both DQ and gluten molecules are necessary for this defense mechanism to start.

Oats are rare to cause celiac, although they often contaminate during processing. In fact, celiac patients are allowed up oats in their diet up to 70 g per day for adults and 25 g for children [Reference: Food Allergy, 4th Edition].

Oats are more distantly related and the gluten-equivalent proteins, called avenins, are extremely rare to cause celiac, especially in moderation.

Food Allergy: Adverse Reactions to Foods and Food Additives, 4th edition. Edited by Metcalfe, Sampson, and Simon.

Celiac Disease by Fasano et al in New England Journal of Medicine, 2012, vol 367, pages 2419-2426.

Mayo Clinic: Overview of celiac disease.

The Celiac Disease Foundation.

NIH: Genetic Home Reference for Celiac Disease and Genetic Risk.

Celiac Disease Diagnosis: Simple Rules Are Better Than Complicated Algorithms by Catassi and Fasano in The American Journal of Medicine, 2010, vol 123 (8), pages 691-693.

Celiac disease: pathogenesis of a model immunogenetic disease by Kagnoff in The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007, vol 117(1), pages 41–49.

Estimated food allergy prevalence rate by Scott H Sicherer in ‘Epidemiology of food allergy’, J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2011, vol 127, page 594-602

Prevalence and Severity of Food Allergies Among US Adults by Gupta et al in JAMA Network Open, 2019, vol 2, page e185630

Food allergy and intolerance by Hodge, et al in Australian Family Physician, 2009, vol 38 (9), pages 705-707.

Evidence for a primary association of celiac disease to a particular HLA-DQ alpha/beta heterodimer by Sollid et. al. in Journal of Experimental Medicine, 1989 vol 169 (1), pages 345-350

Ages of celiac disease: From changing environment to improved diagnostics by Tommasini et. al. in World Journal of Gastroenterology, 2011, vol 17 (32), pages 3665-3671.

New tool to predict celiac disease on its way to the clinics by Sollid and Scott in Gastroenterology, 1998, vol 115 (6), pages 1584-1586.