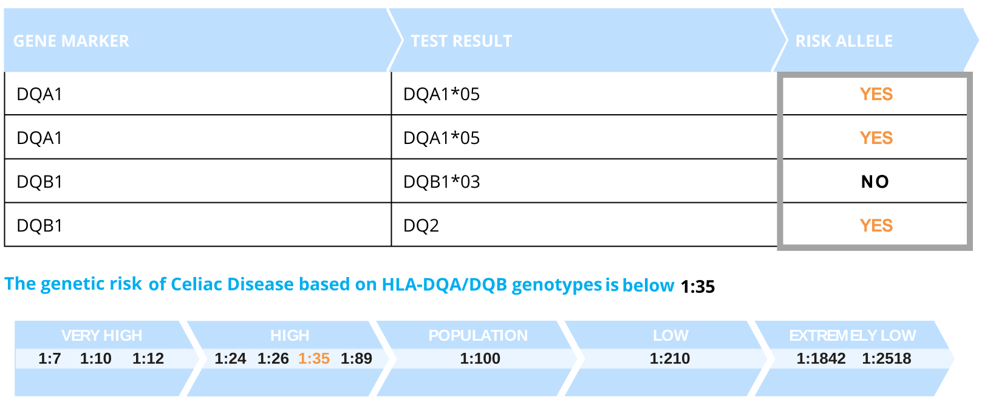

Ordering a celiac genetic test is the first big step in learning about your genetic risk.

If you have already taken this step, congratulations! If not, the information below should help you make a decision.

Celiac is a hereditary disease, with genetic contribution from one or both parent.

First, a certain amount of technical jargon is expected. Let that not discourage you.

For example, your results may be described as ‘probability’, ‘risk of 1 in 100’, 'percentage' or as ratios such as '1:100'. As first, this seems complicated.

In reality, it is telling your risk of celiac relative to the general population, by comparing your results to a group of people studied so far.

Let's take an example to show why it is important.

The risk of celiac disease in US and Western Europe is about one percent or 1 in 100 people.

If your results show 0.5 percent (or 0.5 in 100—which is effectively 1 in about 200 people), you are at lower risk than an average person.

Second, we still don't know a lot about celiac. But the relative predictions help us assess how severe your risk might be, in comparison to an average person.

Finally, the ongoing research in understanding the role of genes is growing rapidly. That's why it is such an exciting time to learn about genes and how they impact our health.

This article will walk you through the basics of genes, their similarity to reading a book, and how they work to cause gluten intolerance.

Genes are not the only factors determining our health in general, or gluten allergy, to be more specific. In fact, for celiac, at least 4 out of 5 conditions are necessary to confirm a positive diagnosis of the disease.

Presence of genes is a must, but there is no guarantee you will have celiac even if you carry the genes. In fact, most people live a normal healthy life despite testing positive for certain celiac genes.

A recent Harvard study looked at data of 40 million Americans and concluded that, at most, genes could only explain about one-third of their health conditions.

Often, more than one gene might be responsible. What if the impact of that second gene is not even discovered yet?

But our knowledge of genetics is growing rapidly and that's why everyone is excited about finding about themselves.

Today, the presence of a gene can be determined with high accuracy.

Since the first complete sequence of human genome in 2003, the technology has become powerful and less expensive over time. In Jan 2022, a research group at Stanford sequenced a person's whole DNA in a record time of 5 hours. Compare it to the fact that it took several years and over a billion dollars twenty years ago.

Besides whole genome sequencing, confirmation of particular genes can help us make better decisions about our health. For example, when sensitivity to a particular food is observed—gluten in the case of celiac—finding out what the responsible genes do to trigger this reaction allows us to appreciate the importance of health recommendations, such as gluten-free diet.

In the example below, we will walk you through and show how genes trigger such an adverse response. And how inheriting few genes might result in getting sick from something as common as wheat, which billions of people eat everyday.

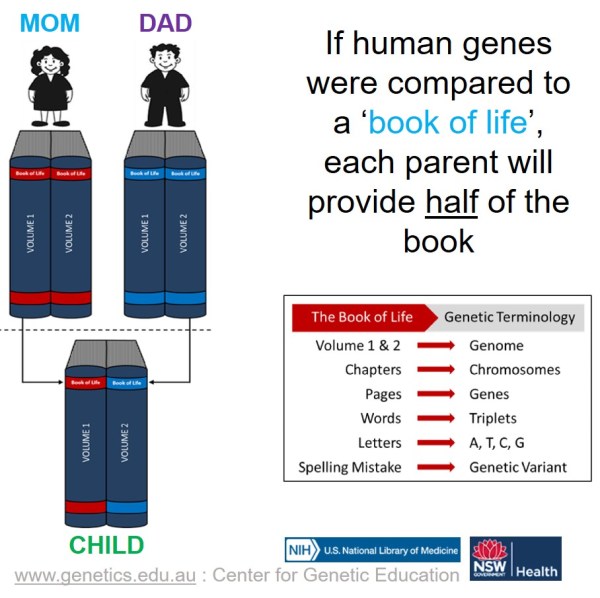

If human genetics were compared to a book, it will have two volumes and each parent will provide one of them.

There will be 23 chapters (same as 23 chromosomes). Half of each chapter will be written by their mother and another half by their father. A page in this ‘book of life’ will resemble a gene in actual life.

Here is an easy, simple way to look at our genes:

In the ‘book of life’, the 23 chapters are the chromosomes. They always occur in pairs as shown in the image below. Each parent contributes one half.

The celiac genes (i.e., the pages with information on celiac sensitivity) are on chromosome six (or chapter 6 of the ‘book of life’).

Here is an image showing the 23 chromosomes. Chromosome # 6 carrying celiac genes on is highlighted.

Inside chapter 6, two pages carry the information necessary to make proteins that bind to gluten and cause gluten sensitivity. The section (or ‘HLA region’ in genetic terminology) that carries the code for gluten reaction is on the short arm of this chromosome.

The DQ HLA regions are the ‘pages’ specific to celiac. Your celiac genetic test report tells whether you have these pages or not.

Shown here are celiac genes on chromosome # 6, marked as DQ on HLA region:

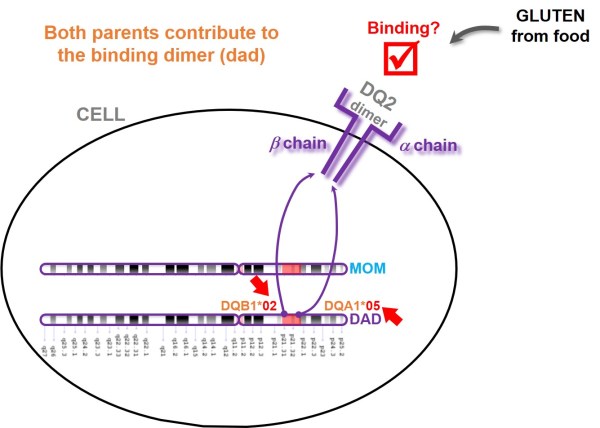

The DQ ‘pages’ in the ‘book of life’ make the protein that binds with gluten. This binding is necessary for immune cells to respond and cause gluten allergy.

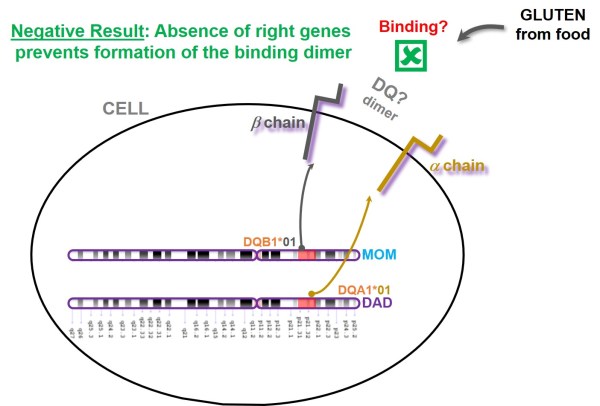

It’s important to note: if you don’t have appropriate pages in the ‘book of life’ (i.e., genes), you can’t make proteins that eventually cause the allergy.

The specific protein that binds to gluten is a dimer (it has two arms). Both arms can be made in several different ways:

1. One arm (α chain) is made by the DQ ‘pages’ of dad’s chapter and another arm is made by mom’s chapter (β chain); or

2. Both arms are made by mom’s pages; or

3. Both arms are made by dad’s pages

When the same gene appears on both chromosomes (or both ‘chapters’ of the ‘book of life’, it’s called homozygosity. This might have additional impact, e.g., it further increases the risk of celiac.

Here is an example when both parents have the genes to form the gluten binding DQ2 dimer molecule:

An example where one parent (e.g., mom) has both genes to form the gluten binding dimer molecule:

Same example as above where dad has both genes to form the gluten binding dimer molecule:

In 5 to 10% cases, a different ‘page’, the DQ8 gene (instead of DQ2) might form the dimer (more specifically, as DQA1*03 and DQB1*03):

You may have celiac genes without any signs of gluten allergy. The reasons for this are not yet completely understood.

However, it is extremely rare (0.04%) to have celiac disease without the relevant genes. That's why, a negative result for celiac genes is extremely valuable.

Without the celiac genes, no dimer can form to bind with gluten and show sensitivity to gluten:

A: No. The genes do not change with or without gluten. The test can be done any time.

A: As long as a parent or guardian is ordering the test, we can test all ages.

A: The sensitivity (truly identifying those who are positive) and specificity (truly identifying those who are negative) are more than 99%.

A: Presence of the DQ2 and DQ8 celiac genes does not mean you will have the celiac disease. The reasons are not yet understood. However, if you do NOT have the genes, it’s almost certain you will NOT have celiac disease (over a life-time, risk of celiac without the genes is 0.04%).

A: About 1 in 100 people in US and Europe have celiac disease. But it clusters around families. Almost 50% of first-relatives have the genes that may cause gluten intolerance. Also, not everyone is diagnosed (that’s why the silent, invisible cases result in so called ‘celiac iceberg’—only the tip is visible despite a very high prevalence).

A: When both parents have the celiac genes, they are homozygous (otherwise heterozygous). This tends to increase the risk.

A: We have reviewed the current research on celiac and summarized the findings in FAQs, historical evidence, and reviewed the research on genetic risk. If you have more questions about your celiac genetic report, you can always contact us.

Human Genome is similar to a book of life, both parents contributing one-half [Center for Genetic Education, New South Wales Department of Education, Australia].

HLA-DQ and risk gradient for celiac disease by Megiorni et. al. in Hum Immunol, vol 70, pages 55-59, 2011. (Full article)

Genetics of Celiac Disease – the Genetic Home Reference by NIH, US National Library of Medicine.

A detailed review of symptoms, diagnosis, testing, management and clinical characteristics of celiac disease by Gene Reviews.