Here we discuss the role of APOE gene in Alzheimer's disease and longevity.

It is common to see people living up to the age of 80 or 90 years today.

This wasn’t the case hundred years ago, not even few decades ago.

The average life expectancy in 1920 was an barely 21 years in India, 40 years in Japan, and 54 years in USA.

Today, a woman in Hong Kong is expected to live an average age of 88 years. Japan, Switzerland and Norway have similar life-spans for women and men.

Most of this is due to advances in treatment of diseases. And huge expenditure in public health as well as management of chronic conditions. What used to kill people regularly–heart attack, diabetes, bacterial and viral infections–can be managed today. That has helped in extending our longevity.

In recent times, the first argument about aging was made in 1889, by Alfred Russel Wallace—a colleague of Darwin—who argued that when human beings “have provided a sufficient number of successors,” there are no reason for them to live long and consume the scarce resources.

His contemporary, August Weismann, proposed a different theory. It says that natural selection works to prioritize survival of the whole species—not an individual. Therefore, a person’s lifespan can be longer as long as they can adapt to the environment. His argument suggested genetics should play a considerable role in this adaptation.

Because people didn’t live long enough until recently, there wasn’t a way to prove how genes affect longevity and aging.

Strong evidence is now accumulating in support of this theory that genes play in important role in longer lifespans.

Siblings of centenarians (i.e., those living 100 years or longer) have four-times higher chances of living up to their nineties.

Studies of twins show reasonable evidence that long life span can be passed on to children.

Detailed genetic analysis suggests a handful of genes play major role in inheriting long life spans.

As life spans increased in past few decades, Weismann’s idea of adaptation to the environment is clearly at play.

It hasn’t been all that rosy though. With this increased life span, a new challenge of cognitive decline has emerged.

Health conditions of the mind, such as Alzheimer’s Disease and dementia are emerging during these late years. Very little knowledge is available today in the understanding of these conditions—let alone any cure—but efforts are growing.

Many experts and public health researchers believe Alzheimer’s might be the next diabetes. It will affect a large population and drain valuable resources in coming decades.

Fortunately, the recent research in genetics suggests it’s not all bad news. A steady pace of understanding has evolved to demystify a close correlation between certain genes and cognitive decline.

We have a long way to go see the full picture. However, evidence that certain genes might increase the risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and early onset of dementia is emerging.

Once such gene is called apolipoprotein E or APOE gene.

Normally, the APOE gene is responsible for making proteins that maintain cholesterol levels in our blood. That's why it isn’t surprising that APOE plays important role in inheriting the risk of cardiovascular disease.

More importantly though, research has shown that it also helps clear the amyloid plaques in the brain. Gradual accumulation of such plaques results in damage to neurons and a slow progressive decline in brain activity.

There are three versions of the APOE gene: E2, E3, and E4. Since we get one gene from each parent, the APOE genes appear in pairs. Several in depth studies have shown that E4/E4 pair has the highest impact on mental decline with age.

The amyloid plaques are the hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. That’s because APOE4 gene aren’t as effective as others in clearing them.

A new study says almost everyone carrying a pair of APOE4 had amyloid plaque build up in their brains by the age of sixty-five.

APOE3 is the most common gene: 3 out of every 4 people carry them. However, APOE2 version is more beneficial. It helps clear the amyloid plaque and reduces risk of Alzheimer’s disease as well as early-onset of dementia.

Data from recent genetic studies have found those carrying E4/E4 pair show unexpectedly higher rates of Alzheimer’s Disease at 91%—a fifteen-fold increase compared to general population.

The condition might start in late sixties, which is earlier than usual.

Among those carrying only one of the E4 genes, this rate is 47% and age of onset around 75 years.

In contrast, those carry E2/E2 pairs have barely 20% chance of Alzheimer’s. And a very late age of about 84 years to see the signs.

One analysis demonstrates APOE4 enhances damage to the blood-brain barrier leading to Alzheimer’s disease.

The latest study in 2024, shows almost everyone carrying two APOE4 genes had signs of Alzheimer's. The early onset of disease was 65 years, earlier than for APOE3 and APOE2.

Some progress in uncovering the roles of other factors has highlighted a much more complicated picture. For example, some genes might negate the E4/E4 curse. This might help explain why not all societies see this universal decline. And previously unknown yet unrelated effects are being reported.

A 2020 study from Stanford University suggests the presence of single gene of KLOTHO in E4/E4 group might help in better clearance of amyloid plaques and reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease. This longevity gene has links to memory and learning enhancement.

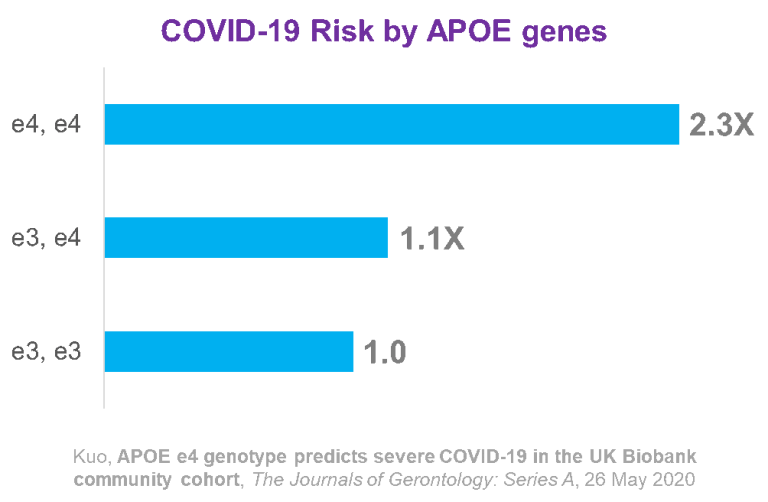

APOE4 has also played an important role during the COVID-19 pandemic. Multiple studies show higher risk and severity of disease in presence of APOE4. Analysis of UK Biobank genetic data concludes E4/E4 pair increases risk of severe infection by two-and-half times.

Source: APOE e4 Genotype Predicts Severe COVID-19 in the UK Biobank Community Cohort by Kuo et. al. in The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 26 May 2020.

With current advancement in genetic testing, it’s easy to test for APOE. An at-home APOE test using a simple cheek swab allows assessing the risk of pre-Alzheimer’s disease and early onset of dementia, before any signs of cognitive decline.

There is no cure for Alzheimer’s yet. But knowing the risk can motivate people in making changes to their life style. Those are still a much more significant risk factors in comparison to the genetic risks we inherit.

Order an at-home APOE gene test kit.

APOE and Correlation to Alzheimer's, CVD, and Dementia - Learn more about the risks from APOE genes in detail.

APOE4 and Alzheimer’s - FAQs - ApoE4 is the biggest predictor of Alzheimer's disease.

Genetic Testing and Disease Inheritability - How to know genes affect the diseases we inherit.

Genetic Variants of Heart Disease - Look at all the markers responsible for affecting heart health.

Celiac Disease and Genetic Risk - Celiac is one of the diseases with very clear genetic causes.

How to Read a Celiac Genetic Test Report - Learn which genes you have that can cause gluten allergy.

MTHFR gene and Heart Health - Learn more about risks due to certain MTHFR genes to your heart.