This summary includes research published in peer-reviewed journals including Frontiers in Bioscience, Archives of Internal Medicine, Physiological Reviews, and more.

We humans differ from animals and birds in a unique way: we can maintain a constant body temperature and don’t require hibernation or migration to warmer climates.

As simple as this may sound, maintaining body temperature has taken millions of years to evolve.

Beyond a certain amount of heat generated from metabolism, we require a system that can generate additional heat in order to raise body temperature (e.g., to 37° C or 98.6° F for humans and 42° C for birds).

During cold, as outside temperature drops, blood vessels shrink to reduce heat loss and we tend to curl up like a sphere, to minimize the exposed area of the body (that's because a sphere has minimum surface area for a given size).

In parallel, our body starts generating heat. At first by shivering, but then the baseline metabolic rate increases. Over time, brown fat deposited around vital organs such as kidney, spinal cord and blood vessels starts to generate enough heat to raise the body temperature.

What if it's hot and the outside temperature is too high?

We have developed unique processes to dissipate heat and lower the body temperature.

Sweating, and slowing down certain biological processes, to reduce heat generated in the body are just few examples to cool down. (That’s one reason why people eat spicy food in hot climates, because it increases sweating, which cools the body.)

The baseline metabolic rate, or BMR, is the lowest amount of energy necessary to stay alive. This would ideally be the minimum energy our body needs.

It is measured at rest, after a meal, and at ambient temperature when no work is needed to heat or cool the body in response to outside temperature fluctuations.

Since we often live indoors at 20-25° C, our body is constantly burning stored fat to keep the temperature at 37° C (or 98.6° F).

In animals that live in cold environments, more bodily heat is necessary to maintain the temperature. It comes from a higher baseline metabolic rate and constant heat generated from the stored fat.

The baseline metabolic rate—sometimes also called, resting energy expenditure—depends on size, genetics, and many other factors including age, pregnancy, and gender.

But heat generated is related to body size. This plot below from a classic 1947 paper shows larger the animal, higher the heat generated with a faster metabolic rate.

But how does thyroid help raise body temperature?

Thyroid is one of the main knobs to maintain a tightly controlled temperature around 37° C (or 98.6° F).

Even birds and other mammals use thyroid hormones to balance their body temperature.

During hot or cold weathers, a fine tuning of thyroid hormones, T4 and T3, balances the heat generated by our bodies.

In hot weather, when outside temperature rises above body temperature, release of Thyroid stimulating hormone, TSH, slows down. Next, T4 and T3 already circulating in the blood exchange an iodine atom to convert into non-active forms, e.g., T4 into reverse T3 (rT3).

What happens if the system malfunctions and the body continues to produce thyroid hormones?

Hyperthyroidism is such a condition when excess thyroid hormone, T4, circulates in the blood. As a consequence, the body constantly struggles to lower the temperature. That's the cause of common symptoms of hyperthyroidism: fatigue, high sensitivity of heat, irritation, and weight loss.

On the other hand, in hypothyroidism, our body can not supply enough thyroid hormones to maintain the temperature. A typical symptom is continuous feeling of cold.

Initially, TSH levels rise (or drop) to maintain sufficient T4 and T3 levels. However, beyond a certain level when TSH levels saturate (or bottom out), the system malfunctions, resulting in a thyroid disorder.

The so called brown adipose tissue—the brown fat distributed around key organs such as liver, heart, kidneys, etc.—is one of the key players in maintaining body temperature. On exposure to cold, these BAT cells generate the necessary heat to raise the temperature.

In hypermetabolic state—in hyperthyroidism—resting energy spend increases, people lose weight, their cholesterol levels drop, brown and white fat burning increases, and a higher blood sugar appears. These processes reverse in case of hypothyroidism.

Technical info – how a signal of feeling cold, translates into heat generation in the body?

As soon as the skin senses cold, blood vessels shrink, and the sympathetic nerves send signal to hypothalamus. This causes shivering, and the brown fat surrounding blood vessels and key organs receive signal to activate their adrenaline receptors (norepinephrine). This results in fat burning (lipolysis) to release heat in the body. Thyroid hormones and the uncoupling protein (UCP1) rapidly activate by lipolysis and the cell mitochondria oxidation causes generation of heat.

Have you noticed the feeling of slump after a meal?

That’s because carbohydrate metabolism and the resulting insulin act as a switch to activate the enzyme responsible for body heat generation.

Fasting slows down the supply of thyroid hormones to avoid any fat burning in the body—a behavior similar to hypothyroidism.

In diabetes, the insulin resistance affects body’s ability to stay warm through heat generation from the process of burning brown fat tissues. The new miracle weight loss drugs that use GLP-1 pathway follow a similar approach, but need more understanding.

In animals that have thyroid dysfunction—or can not properly control the process of fat burning to generate heat—continuous eating is necessary to keep them warm.

During extreme starvation, the body shuts down this heat producing mechanism. Similar slow down occurs in hibernation, which is also mediated by thyroid hormones.

Thyroid hormones play a key role in controlling metabolism together with brain, white fat, brown fat, skeleton muscles, liver, and pancreas. That’s why they are considered potential paths to solve the metabolic disorders related to obesity, diabetes, and high cholesterol. A thyroid test is one of the first step to understand the underlying issues.

Low thyroid hormone levels are also associated with retaining water in the body.

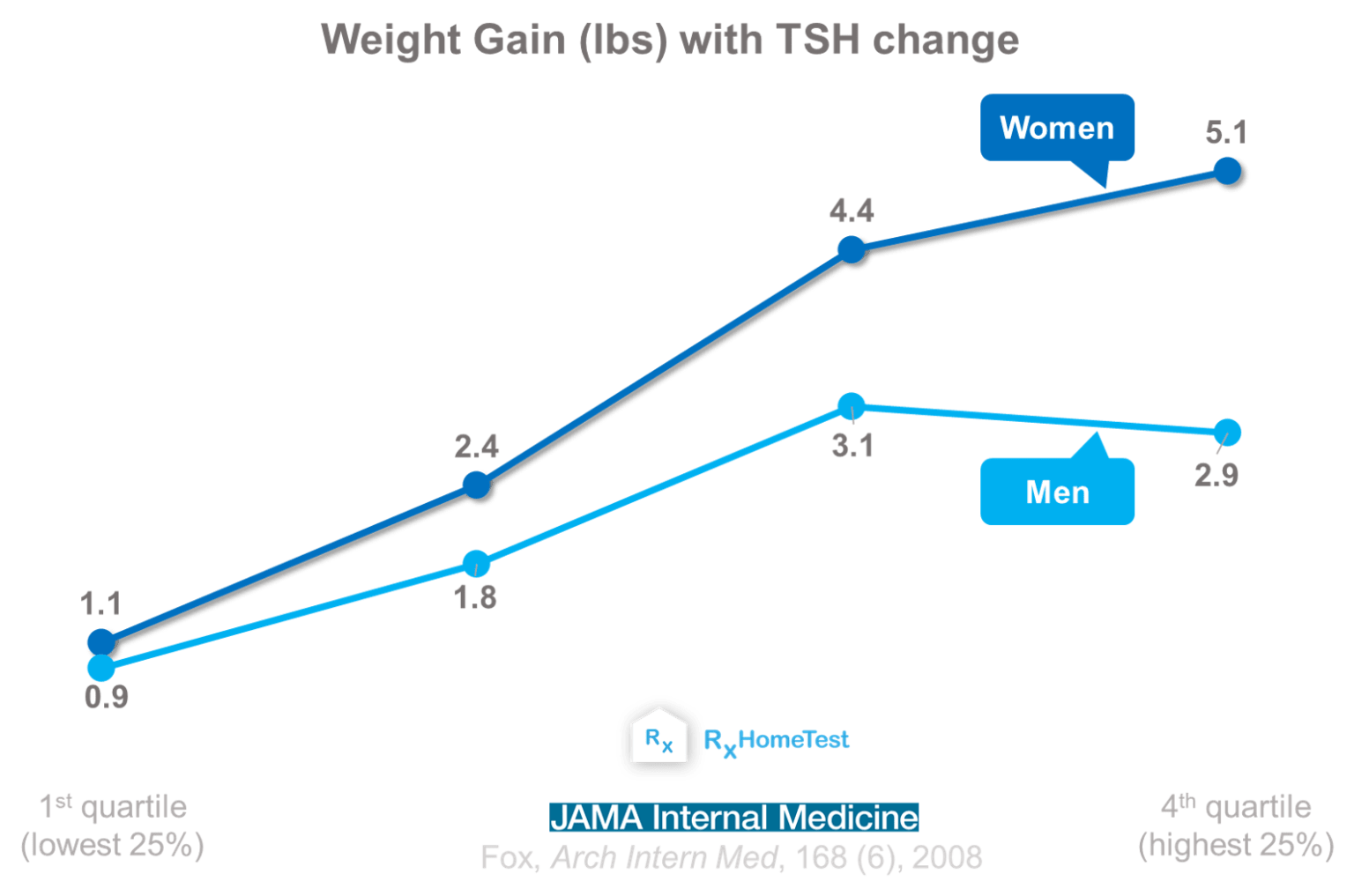

After treatment, release of this excess water results in weight loss (but amount of fat generally remains the same). It also seems to vary between men and women, as plot on top of this article shows.

Studies suggest hyperthyroidism increases craving for carbohydrates which returns to normal after treatment of high thyroid hormones levels.

Interestingly, T3 is about ten-times more active than T4 in the body. That’s why it is seems to be more effective in weight loss and lowering cholesterol. However, no effect on insulin or cardiovascular health occurs.

Who would have thought: A tiny gland in the throat has developed into a vital organ to maintain such a complex system of temperature control. It is truly an amazing feat of evolution.

Order an at-home thyroid test.

All About Thyroid - an in depth summary.

Normal TSH Levels: What's Normal and Why? - a detailed look at thyroid stimulation hormone.

5 Common Thyroid Problems to Watch Out for - read about most common problems with thyroid.

5 Signs You Should Take an At-Home Thyroid Test - symptoms before testing for thyroid disorders.

Tips for Understanding Your Home Thyroid Test Results - a few quick tips after you complete the test.

Thyroid Hormones During Pregnancy - about the critical role thyroid plays during pregnancy.

Thyroid and the Key Role of Iodine - thyroid problems depend on lack or excess of iodine.

How the Brain Controls the Thyroid - basic concepts about thyroid and brain synergy.

Thyroid Hormone Regulation of Metabolism by Rashmi Mullur et. al., Physiological Reviews, Apr 2014.

Physiological importance and control of non-shivering facultative thermogenesis by J. Enrique Silva, Frontiers in Bioscience, Jan 2011.

Relations of Thyroid Function to Body Weight: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Observations in a Community-Based Sample by Fox et. al., Archives of Internal Medicine, Mar 2008.

Mechanisms of thyroid hormone action by Gregory A Brent, The Journal of Clinical Investigation, Sep 2012.